(This is an updated version of a note originally posted on LinkedIn in November 2016.)

A long-held view by some investors is that governments rarely default on local or domestic currency sovereign debt.[1] After all, they say, governments can service these obligations by printing money, which in turn can reduce the real burden of debt through inflation and dramatically so in cases like Germany in the 1923 and Yugoslavia in 1993-94.

Of course, it’s true that high inflation can be a form of de facto default on local currency debt. Still, contractual defaults and restructurings occur and are more common than is often supposed. A key objective of our ongoing work compiling and updating the Bank of Canada’s sovereign default database (available at http://www.bankofcanada.ca/2014/02/technical-report-101/) is to identify and document such cases for 1960 – 2016, the timeframe covered by the 2017 vintage of the database released on 30 June 2017.

We’ve previously highlighted that documenting local currency defaults is challenging because they are rarely acknowledged as such by the governments concerned. But there is another factor that has likely contributed to the reduced visibility of many local currency defaults – the investors affected were (and are) mostly domestic residents with limited avenues of redress. Cross-border investment in sovereign local currency debt instruments, a phenomenon dating back to the 1990s, has contributed to broader awareness of more recent default cases.

So far, we have identified 27 sovereigns involved in local currency defaults between 1960 and 2016. These defaults have taken different forms. Perhaps most surprising is the number involving demonetisations of central bank notes on confiscatory terms. We reckon that 17 sovereigns have undertaken such exchanges, with some (e.g. USSR/Russia, Myanmar, North Korea and Ghana) doing so more than once. Losses occurred when mandated exchanges of bank notes occurred over short periods, when they placed limits on the amounts of old notes that could be exchanged for new notes, when excess notes were required to be deposited in blocked accounts, and when foreign holders of banknotes were prohibited from participating in the exchanges.

Confiscatory currency reforms appear to be idiosyncratic in nature – often the result of regime changes and/or efforts by centrally planned governments to curb black markets. In most cases, domestic capital markets were either underdeveloped or non-existent, and so bank note exchanges were not always an indicator of broader fiscal distress. Indeed, among these 17 sovereigns so far we have identified just two cases (Nicaragua and Russia) where the government defaulted on other types of local currency default, although many more ultimately defaulted on foreign currency obligations owed to official and private creditors. The local currency defaults involving nine other sovereigns included arrears on scheduled interest and principal payments, restructurings of maturities, unilateral reductions in real interest coupons and maturity extensions on inflation-linked debt, and the imposition of taxes targeting local currency debt service.

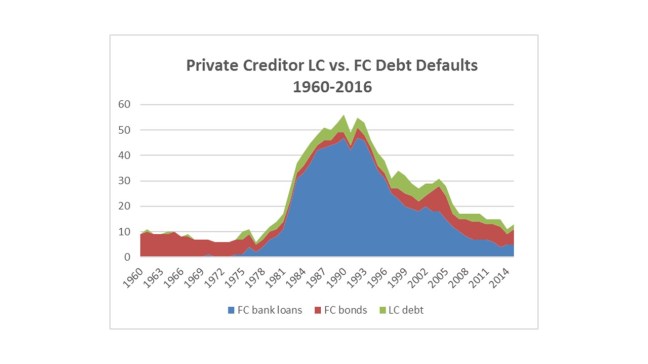

The chart above tracks the annual number of defaults on local currency debt we’ve identified compared with defaults on foreign currency bank loans and bonds, the two other main categories of sovereign debt owed to private creditors. Over nearly half the survey period, defaults on foreign currency bank loans predominated. But in the past twenty-five years, as banks pulled back from sovereign lending, defaults on foreign currency bonds have increased, as have, to a lesser extent, defaults on local currency debt. In the past decade, between 4 and 8 sovereigns per year have been in default on foreign currency bonds, and between two and three sovereigns per year for local currency debt.

Interestingly, defaults on foreign and local currency debt by the same sovereign have happened concurrently less than half of the time. Looking ahead, though, debt dynamics may be shifting. With public debt burdens of many advanced and emerging sovereigns increasing at the same time as cross-border investment, defaults on local currency debt could become more frequent and as common as defaults on foreign currency bonds. In the meantime, though, there is one caveat. And that is that our understanding of the past may need to be revised if and when more historical local currency defaults are identified.[2]

We’ll continue to keep you posted on our work ahead of publishing the next vintage of the sovereign default database in 2018.

[1] Local or domestic currency debt refers here to obligations issued by a government in its own currency. For sovereigns that are members of monetary unions, debt denominated in the common currency is regarded as foreign currency debt in our analysis.

[2] Our efforts to identify local currency defaults currently focus on securitized debt. In other words, we exclude some types of domestic fiscal arrears — unpaid supplier invoices, salaries, and pensions — even though, when lawfully contracted, they too are government obligations. With that in mind, we are considering including them in future updates of the sovereign default database.